Mahua: A Deep Dive Into India's Traditional Drink

2026-01-29

Brandy, the spirit distilled from either wine or fermented fruit juice, is heavily defined not only by the grapes or fruit that are used but also, importantly, by the process of distillation. The aging process in an oak barrel is critical to the final smoothness and character of the spirit, as is the still through which it passes. Distillation is so essential that the type of still used and the way it is used can affect the complexity, aromatics, and flavor profiles of the spirit.

There are two main distillation methods produced commercially, which are copper pot stills and continuous stills (also known as column stills or patent stills). Both distillation methods have their own qualities to the spirit, one emphasizing depth and the maker's mark, and the other emphasizing purity, lightness, and speed of distilling.

In this article, we will explore the science and art of pot still distillation and the science and artistry of column still distillation, review their differences, and understand how distillers make the decision between the two systems of distillation when making their products.

Prior to undertaking a comparison of pot still and column distillation, let's quickly review the end product of distillation. Distillation is, at its essence, the heating of a liquid mix (wine, in the case of brandy) such that the most volatile components, such as alcohol and various other volatile compounds, are evaporated while water remains. The vapor is then condensed to form a liquid.

But distillation is more than just a means of concentrating alcohol: distillation is also a means of controlling which congeners (flavor and aroma-delivering compounds) are retained, as these congeners include:

The type of still used plays a key role in how many of these compounds are retained—or stripped away.

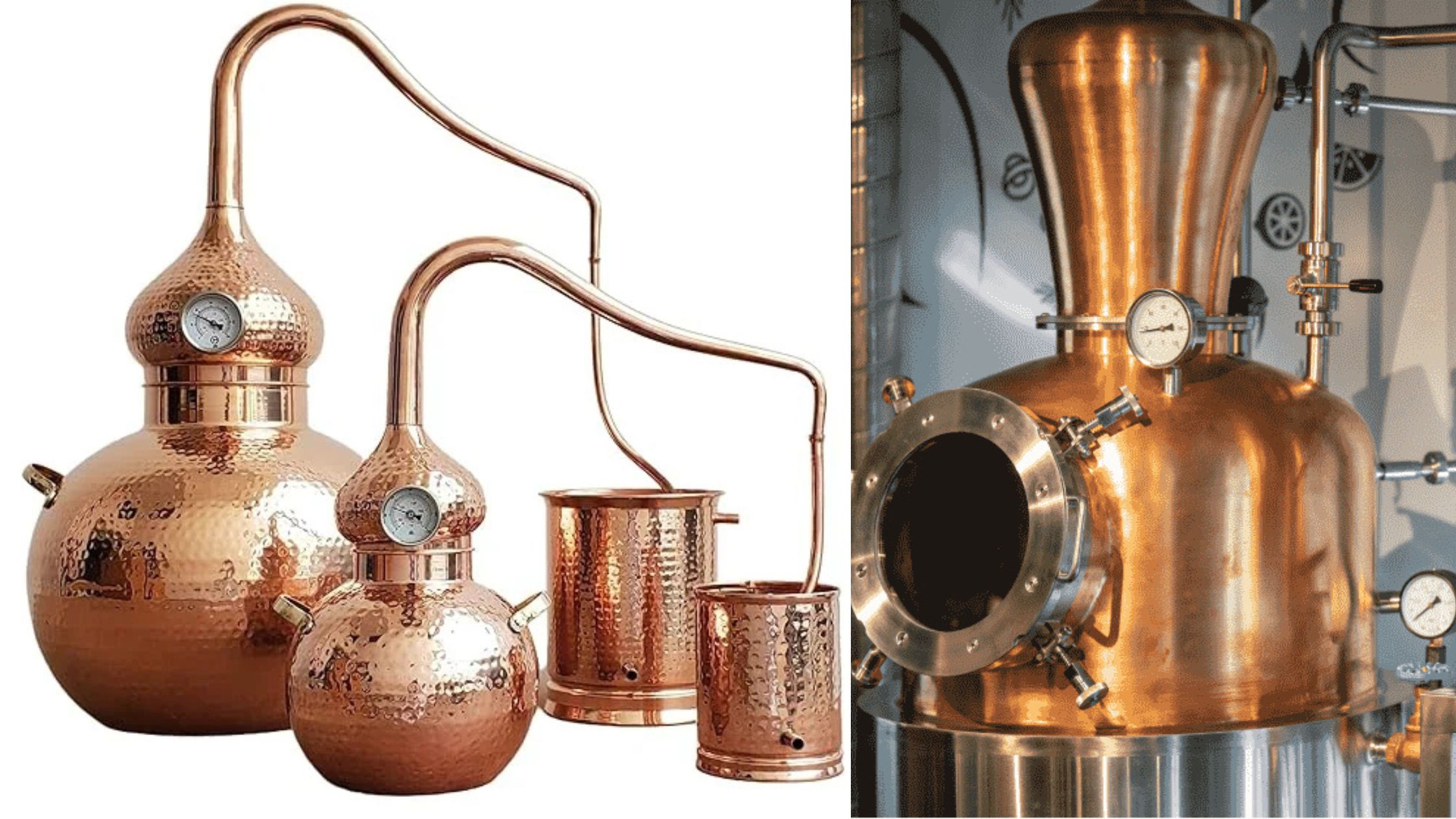

A copper pot still is arguably the most recognizable image of distillation: a bulbous copper structure with a long neck resembling a swan's neck, usually shining bright from the lights of a distillery. The pot still is designed for batch distillation, meaning we only distill a fixed volume of liquid where the still is emptied, cleaned, and unbelievably back to top shape before the next run.

Copper isn’t just for aesthetics. It actively reacts with sulfur compounds released during fermentation, removing unwanted harshness. Without copper contact, brandy (or any spirit) can taste rubbery, sulfury, or even metallic.

Because pot stills are less efficient than column stills, they allow more congeners to pass through into the final distillate. This means:

French Cognac regulations require distillation in copper pot stills. This explains why Cognac tends to be complex, aromatic, and full of depth compared to lighter, industrially produced brandies.

If you were to sketch a pot still diagram, you’d see:

This relatively simple design is precisely what makes pot still distillation so hands-on and variable—an art as much as a science.

On the other end of the spectrum is the continuous still, also known as the column still or patent still. While pot stills are charged and run in batches, column stills are capable of continuous operation, adding fermented wine at one end and taking off spirit at the other.

A column still has a number of plates or trays loaded vertically into a tall column. As the wine comes in and steam rises through the column, the alcohol vaporizes and condenses many times on those plates, essentially distilling the spirit many times in one pass.

Column still brandies tend to highlight:

While they can still produce esters and higher alcohols, the overall intensity and diversity of these compounds is reduced compared to pot still distillation.

Also Read: VSOP Brandy: Meaning, History, and Why It Matters

Here’s a breakdown of the difference between pot still and patent still in terms of flavor and production:

|

Aspect |

Copper Pot Still |

Continuous Still (Patent/Column) |

|

Flavor Profile |

Rich, layered, complex |

Light, clean, less complex |

|

Retention of Congeners |

High |

Low |

|

Production Style |

Batch, artisanal |

Continuous, industrial |

|

Impact on Aroma/Esters |

Higher diversity |

Subtler, less distinctive |

|

Efficiency |

Labor-intensive |

Energy-efficient, high output |

|

Best For |

Premium, aged brandies (e.g., Cognac, Armagnac) |

Affordable, lighter brandies for wider markets |

To illustrate the process of distillation in a relatable way, we can consider the pot still versus column still whiskey conversation.

The same logic holds for brandy in that how the still is made determines if you are getting a more deeply expressive spirit or a clean, easy-drinking one.

The choice between copper pot stills and continuous stills often comes down to three factors:

Modern distillers aren’t limited to just one approach. Many experiment with hybrid techniques:

This experimentation reflects the broader spirits industry, where innovation often coexists with tradition.

The still is the centerpiece of brandy-making, the mechanism that is truly the essence of the spirit.

Neither type is "better", it just depends on whether you want luxury and complexity or affordability and scale.

So the next time you experience the enjoyment of a sip of brandy, whether it is a deep, oaky Cognac or a light, crisp style, you can be assured it all started with the still, where copper, passion, steam, and creativity laid the foundation.

Also Read: The Best Ways to Drink Bourbon: Neat, On the Rocks, or in Cocktails